A Golden Relationship

Blondie: 1981-2021

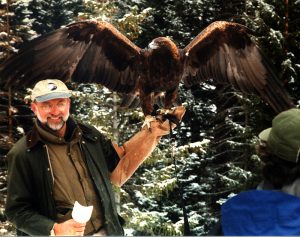

Peter and Blondie at the 1999 World Cup in Beaver Creek, Colorado. Photo by David Sargent

She was only six months old when Blondie adopted REF. I know you might think that is a backwards and foolish statement, but after having worked side by side with her for 39½ years I’m inclined to think she had as much to do with creating our educational efforts, as I did in creating the foundation that would be her showcase for 40 years. Chance plays a major part in what aspects of life we choose to develop or disregard. When Terry Grosz, the USFW Special Agent in Charge of Region 6 asked if I was interested in acquiring a young golden eagle that had failed rehab in Montana, I was somewhat cautious. I knew that imprinted raptors could be a handful to work with, and especially one as powerful as a female golden. But our first golden eagle was not really suitable for the role we had created and we were looking for a golden that was. Little did I know how well she would grow to fill the niche we needed her to, along with another note of gratitude to Terry Grosz.

As we began to work with her, it became quickly apparent that she was just as curious about us as we were about her. She adapted to virtually every situation we introduced her to with the few exceptions Anne describes below. As her relationship with her REF trainers and handlers grew, she matured in her ambassadorial role and became an exceptional representative of her kind.

Throughout all the years we worked with each other, we developed a mutual trust to the point that, in the midst of a program before a large audience at Rockland Community College in New York, while perched on my arm, her body language told me what was about to happen, and I quickly caught the egg she just had just laid. I showed it to the bewildered crowd, which had fallen silent in astonishment, while I described to them what had they had just witnessed. She was like that: she left me feeling like I knew a little something more about her, but in the end, I always felt inadequate in her presence. She, of all the raptors I have had the privilege of working with, connected me to the writings of Henry Beston in his book, The Outermost House:

“We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.”

In the end, she took part of me with her. It was a part I never knew I had until I met her, and with each day that passes, I am that much more diminished by her absence.~Peter Reshetniak, Founder & Director of Special Projects

My favorite photo of the two of us together, at the Beaver Creek Birds of Prey course while waiting for the medal ceremony to begin.

Photo courtesy of Steve Prawdzik,Talon Crew, 2013

I joined REF in the fall of 1986, as a nineteen-year old college student. Majoring in biology at CU-Boulder, I had also been working with raptors for six years and had already worked with two golden eagles. One was a huge female, weighing around fifteen pounds. But she had been blinded in one eye due to a gunshot, and though gentle, she was a nervous bird requiring very careful handling. I had never worked with an imprint eagle before and for the next 34 years, Blondie never ceased to amaze me, and more than once, left me speechless.

She was no ordinary eagle, and not even a typical imprint raptor, as I learned over the decades. It is difficult to express how truly interested she was in what the humans around her were doing, and how much she appeared to “enjoy” being around us. Dozens of volunteers could describe how she grabbed trash bags, played with the hose, tugged on clothing and insisted on coming right up to us to see what we were doing in her enclosure. In zoological terms, her life was just about as “enriched” as any eagle living with people could hope for. But more than this, her behavior in front of an audience was simply extraordinary. Noises and constant movement never bothered her. Sudden noises barely elicited a reaction. Way back in the 1980s and 1990s, we discovered that certain brightly-colored carnival game prizes scared her terribly, but eventually, she adapted and lost her fear of even those crazy toys.

In the fall of 2003, she became sick with West Nile virus. That year, she and six other REF birds became ill, despite being vaccinated, and we lost our male golden eagle who was around 55 years old. West Nile left her blind in her right eye, and with a permanent droop to her wrists due to neurological damage. Again, she adapted beautifully, never losing her ability to fly, never behaving as though she could only see half of what was around her. She continued to be the queen of our mews, her beautiful, clarion territorial call ringing through the sky whenever a wild raptor flew overhead.

Her presence at the World Cup Alpine Ski Championships in Beaver Creek was simply “next level”. Golden eagles are found worldwide in the northern hemisphere, so the elite skiers from around the world as well as local fans, all loved seeing her up close. Folks from Chamonix to Innsbruck to Killington to Gypsum came up to me, year after year, wanting to check in and say just hello to her. We spent hours together, side by side, with cameras and microphones in our faces and snow falling on our heads. One of us smiled and answered questions non-stop, and the other barked at ravens swooping over the finish stadium.

Anne and Blondie at the Northglenn-Thornton-Westminster Water Festival, a day-long event

in which we’ve participated for decades. The faces of the children say it all…

We knew that her bout with West Nile virus would likely shorten her life. But nothing could have prepared us for the behavior change which began on March 21st. By the next day we knew something was terribly wrong. We immediately ruled out egg binding; although she didn’t lay eggs in 2020, she still had a brood patch and was exhibiting her typical “running with sticks” behavior. She had previously laid eggs year every year from 1990 to 2019. She made it through the first night at Anne’s house and we are deeply grateful to Dr. Alison Hazel, and Dr. Kris Ahlgrim of Goldenview Veterinary Hospital for their outstanding and thorough care. By the end of that first week, we determined that Blondie had suffered a stroke or bleed of some kind. Radiographs (x-rays) also showed that her heart wasn’t in the best of shape either, with enlarged veins and arteries. Because the normal lifespan of a wild golden eagle is 20-30 years, we weren’t surprised at any of these findings. Her lungs, muscles and skeleton were in excellent shape without any signs of arthritis. We also performed an ultrasound on her abdomen, and other than a very active ovary, all seemed normal there.

Within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms, she was on heart medication to regulate rhythm and improve blood flow. We soon added Meloxicam, which saved the life of our old female bald eagle from Alaska who also suffered a stroke at age 29. I was hand-feeding her twice a day, and keeping her at a constant temperature of 80F. Almost two weeks later, she ate on her own for the first time and even took a bath. Each day, we watched her regain some strength and I was also helping her re-learn certain behaviors, such as stepping on a scale and jumping up to a perch. Blondie had even lost her voice, as many human patients do, but slowly regained it after about ten days.

Hope can be a wonderful, terrible thing. A recheck on April 15th showed that she had gained half a pound and was very responsive to stimuli. But she was also showing very faint signs of weakness in her left leg, and the exam left her tired for hours afterwards. Over the next two days, she was quiet, and lost some of her appetite. We increased her warmth and kept her indoors but I felt something was wrong. Overnight from April 17-18, she suffered another stroke, or possibly the clot in her brain moved and she lost the ability to control her legs and stand. We knew there was nothing else we could do for her and that we had to let her go, and finally rest. Words cannot adequately express our gratitude to Dr. Matthew Demey of Seven Hills Veterinary Hospital for his caring and gentle medical intervention, with virtually no notice, on a late Sunday afternoon.

Peter was with her for 39½ years…I was with her for 34½. Our profound grief is tempered with deep gratitude for her long and remarkable life. She changed the hearts and minds of ranchers who thought that eagles killed calves and carried away sheep. She made people realize that rabbits and prairie dogs, so often thought of as “vermin” and “disposable” animals, were the primary, critical source of food for her kind. Millions of people over the years looked her in the eye, saw that magnificent 6-foot wingspan, and realized that eagles and all raptors need to be protected. She brought people together and brought the wild world into classrooms and state fairs and churches and so many other places where eagles aren’t supposed to be. We have only ever shared the names of our birds after they have left us, because their lives and circumstances are too important, too serious to be reduced to a “pet” name. The mantra we’ve repeated for 40+ years is, “These birds are not our pets”. But it doesn’t mean we don’t love them, and treasure every moment we are privileged to care for and work with them. We have lost a member of our family and she was a once-in-a-lifetime bird. On behalf of our staff and docents, all of whom share in our collective grief, thank you for reading our tributes and for all your support that helped us care for her for nearly four decades.~ Anne Price, President